Demining Angola

Luanda, the capital of Angola, could be one of the most beautiful port cities in the world …

30 years of civil war created massive slums.

Only nice from a distance: Boa Esperance, a make shift camp for 75,000 refugees.

Long without hope: The children born in camps.

Report

The MgM mine clearance project Bengo

Pre-History

The province of Bengo is the region around Luanda, the capital of Angola. Over centuries Bengo served as the bread-basket of this naval metropolis. The extraordinarily fruitful land allowed Luanda to develop into one of the most impressive cities in Africa. Over and over again hostile armies have tried to capture Luanda and it has always resulted in displacement and agony for the farming population around the city. The last two wars, the liberation from the Portuguese and the resulting on-going civil war, have hit the population extremely hard.

Far away from public view, the global superpowers used Angola as a surrogate battleground into which they dumped their outdated weapon systems in vast quantities. The Angolan people were the pawns in their ideological games. The volume of weaponry, ammunition and land mines spread throughout the country beggars belief. The war became harder and harder for the rural population, undefended against increasing rocket and bomb attacks, so many fled to the relative safety of the cities.

Good Hope

In 1992 the peace treaty between the MPLA government and the rebel organization UNITA fell apart following the first democratic election. As a result, the entire population of central Bengo, called Nambuano, fled to Luanda. They were not allowed into the overcrowded city, so the WFP - the World Food Program of the United Nations, rented a desolate piece of land that became a camp for 75,000 civil war refugees. The name of the camp was Boa Esperanca, Portuguese for "Good Hope". The distribution of food and the retention of town structures in groups of huts were handled by the DWHH, the German World Food Aid organisation.

In 1996, on the initiative of the then German Ambassador in Angola, Mr. Helmut von Edig, the WFP Director Ramiro da Silva and the land coordinator of the DWHH, Dr. Lange, the decision was made so promote the return of the population of Boa Esperanca to their old homes. Nobody knew the situation in central Bengo even though it was only 180 kilometres away from Luanda. Access to the area was totally closed by the fear of mines on the broken and overgrown roads and the impassable bridges. The only available information came from a helicopter flight of one of our Ambassadors with NPA (Norwegian Peoples Aid), and from a map made in 1962.

As long as roads cannot be used, refugee camps remain full, fields remain unplowed and schools remain empty.

Form the junk yards of civil war: Custom made and mine safe military vehicles pitch in for the reconstruction of peace.

An armoured MgM construction vehicle clears the way home for refugees. Even trucks can drive on the jungle road shortly after MgM’s mine clearance is completed.

The beginning of the mine clearing

At the invitation of the foreign office, Referat 300, the newly founded MgM accepted an apparently impossible contract to prepare the entire region for the safe return of the internally displaced people.What followed was a deluge of work under the hardest of circumstances using mine clearing systems specially developed by MgM. Because of dire financial difficulties our machinery was built from war junk and the so-called "experts" shook their heads with disapprovaL. In order to reach the roads to be cleared, bridges in the area had to be cleared from mines and repaired.

Alongside the expected problems of clearing mines in a mountainous tropical rain forest in a fragile time of peace came a tremendous logistical handicap. Materials promised by the German Armed Forces unexpectedly didn't come through. In a unique statement of solidarity the "competition" supplied MgM with a complete set of camping gear, first-aid equipment and even 4x4 vehicles. With such faith in our capabilities and the hopes of thousands of people on our shoulders, there was only one way for us to go. Against all odds, and against the stated will of the government, we opened the roads back home meter by meter, at times even centimeter by centimeter.

First results, new methods

International governments were initially very sceptical of MgM’s unusual methods, but they slowly began to understand and eventually the Dutch government, through their First Secretary in Luanda, Dr. Roderick Wols, offered generous support (both financially and morally) for our combination of timely humanitarian mine clearance and parallel road and bridge repair.

This was the time that MgM coined the terms "integrated" and "mechanically assisted" mine clearance.

What was originally planned as a 12 month project clearing 75 kilometres turned into 2 years and around 260 kilometres of mine free road that was immediately usable again. We found relatively few mines and explosives on the roads themselves, but we found and disposed of veritable mountains of explosives and mines in and around the abandoned towns along the routes.

The refugees are already waiting behind the MgM mine clearing team.

Always surrounded: the MgM ambulance

Patiently the people are waiting to enter the makeshift, repaired and now mine free church.

The return home

The population of Boa Esperanca became increasingly more anxious to escape the camp and when we declared the district capital of Muxaluando free, a seemingly endless stream of displaced people flooded back into that city. They did not wait for marching orders or government trucks. They did not wait for help from other aid organizations. Walking, carrying their belongings on their heads, approximately 60,000 internally displaced people returned home after 7 long years.

People pressed behind our clearance operation by the thousand, and every town declared mine-free was a celebration.

By Christmas 1998 MgM had facilitated the return of all those occupying Boa Esperancas to their homes. The Director of WFP (World Food Program) called the entire operation the only happy return of displaced people that Angola had witnessed at that time. He was right, and unfortunately this is still true today.

First Aid

Having nowhere else to turn, large numbers of people came to the MgM camps looking for medical aid, especially during pregnancies and following the accidents which occurred regularly during the erections of huts. Just as our medical staff were ready to collapse under the pressure of up to 400 patients a day, Johanniter Unfallhilfe came to the rescue with personnel, equipment and medication.

We stood by the population day and night, every suspicious looking object would be secured by our fire-fighters, the street clearing machines created soccer fields, the deminers gave Mine Awareness classes under trees (schools!) and our administration (a laptop) was used to compose letters asking for help from the provincial government.

Wells, water holes, school, churches, first aid posts, cemeteries, houses, huts, gardens, plantations, windmills, bus stops, markets, paths - all suspect places were cleared and repaired by MgM teams.

Many children were born while we were stationed there and quite a few now boast the fashionable name "Em-Jee-Em" or are named after the two MgM founders who were on-site running the operation.

On the streets and roads of Bengo province, the children can once again play without danger.

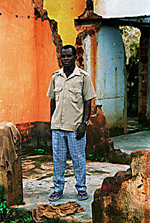

Hard to believe: amongst the sad rubble this man is happy. He’s been waiting for years to start re-building his house. After MgM had declared the rest of his village mine free the future of his family once again lies in his hands. A stroke of luck that makes him the envy of many in Angola.

No accidents, no victims

A little later, the civil war once again entered a more ferocious phase and we had to withdraw our teams from Nambuangogo. We made a pit stop on the coast of Libongos and Ambriz.

The work in Nambuangongo is only 95% complete, but as of today all the people who returned home have stayed, all roads are in use and there has not been a single mine or ammunition incident in the areas cleared by us.

Interim Balance

If one assesses the value of the programme in terms of the cost of lifting each mine on the roads, the detection and destruction of every mine cost around DM 50,000. However, if one assesses the value in terms of the number of people that the programme helped to safely return home, the cost was around DM 50 person. Even a single mine could make 100 kilometres of road impassable. This is why the number of mines cleared is not as important as the social benefits of clearing them.

The people who have returned to Nambuangongo no longer have to depend on DWHH and WFP for food, or on MgM for other help.

Unfortunately, today the camps at Luanda are full of displaced people again, this time from the region of Dembos. The MgM projects for 2001 are looking at ways to bring about a safe return for these 30,000 victims of the Angolian civil war.

Whether MgM can achieve this difficult but urgently needed humanitarian mine clearance project depends especially on the continued support of our members.

We will post any updates on the further development of this project here.